Daboia

| Daboia | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Viperidae |

| Subfamily: | Viperinae |

| Genus: | Daboia Gray, 1842 |

| Species: | D. russelii |

| Binomial name | |

| Daboia russelii (Shaw & Nodder, 1797) |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Daboia is a monotypic genus[8] created for a venomous viper species, D. russelii, which is found in Asia throughout the Indian subcontinent, much of Southeast Asia, southern China and Taiwan.[1] Due largely to its irritable nature, it is responsible for more human fatalities than any other venomous snake.[9] Within much of its range, this species is easily the most dangerous viperid snake and a major cause of snakebite injury and mortality.[2] It is a member of the big four venomous snakes in India, which are together responsible for nearly all Indian snakebite fatalities.[10] The species was named in honor of Dr. Patrick Russell (1726–1805), who had earlier described this animal, and the genus after the Hindi name for it, which means "that lies hid", or "the lurker."[11] Two subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.[12]

Contents |

Description

This snake grows to a maximum length of 166 cm (5.5 ft). The average length is about 120 cm (4 ft) on the mainland, although island populations do not attain this size.[2] It is more slenderly built than most other vipers.[13] Ditmars (1937) reported the following dimensions for a "fair sized adult specimen":[14]

| Total length | 4 ft., 1 inch | 124 cm |

| Length of tail | 7 inches | 18 cm |

| Girth | 6 inches | 15 cm |

| Width of head | 2 inches | 5 cm |

| Length of head | 2 inches | 5 cm |

The head is flattened, triangular and distinct from the neck. The snout is blunt, rounded and raised. The nostrils are large, in the middle of a large, single nasal scale. The lower edge of the nasal touches the nasorostral. The supranasal has a strong crescent shape and separates the nasal from the nasorostral anteriorly. The rostral is as broad as it is high.[2]

The crown of the head is covered with irregular, strongly fragmented scales. The supraocular scales are narrow, single, and separated by 6–9 scales across the head. The eyes are large, flecked with yellow or gold, and each is surrounded by 10–15 circumorbital scales. There are 10–12 supralabials, the 4th and 5th of which are significantly larger. The eye is separated from the supralabials by 3–4 rows of suboculars. There are two pairs of chin shields, the front pair of which are notably enlarged. The two maxillary bones support at least two and at the most five or six pairs of fangs at a time: the first are active and the rest replacements.[2] The fangs attain a length of 16 mm in the average specimen.[15]

The body is stout, the cross-section of which is rounded to cylindrical. The dorsal scales are strongly keeled; only the lower row is smooth. Mid-body, the dorsal scales number 27–33. The ventral scales number 153–180. The anal plate is not divided. The tail is short — about 14% of the total body length — with the paired subcaudals numbering 41–68.[2]

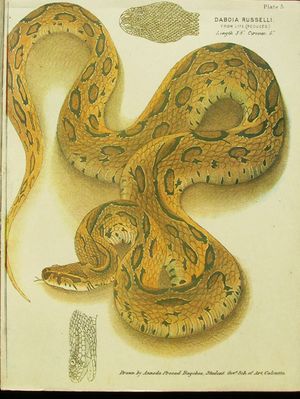

The color pattern consists of a deep yellow, tan or brown ground color, with three series of dark brown spots that run the length of its body. Each of these spots has a black ring around it, the outer border of which is intensified with a rim of white or yellow. The dorsal spots, which usually number 23–30, may grow together, while the side spots may break apart. The head has a pair of distinct dark patches, one on each temple, together with a pinkish, salmon or brownish V or X pattern that forms an apex towards the snout. Behind the eye, there is a dark streak, outlined in white, pink or buff. The venter is white, whitish, yellowish or pinkish, often with an irregular scattering of dark spots.[2]

Common names

- English – Russell's viper,[2] chain viper,[4][5] Indian Russell's viper,[6][7] common Russell's viper,[16] seven pacer,[17] chain snake, scissors snake.[18] Previously, another common name was used to described a subspecies that is now part of the synonymy of this form: Sri Lankan Russell's viper for D. r. pulchella.[16]

- Urdu, Hindi, Hindustani, Punjabi – daboia.[19][15]

- Kashmiri – gunas.[15]

- Oriya – Chandra Boda

- Sindhi – koraile.[15]

- Bengali – bora, chandra bora, uloo bora.[15]

- Gujarati – chitalo, khadchitalo.[15]

- Marathi – ghonas.[15]

- Telugu – katuka rekula poda.[15] or raktha penjara/penjari.

- Kannada – mandaladha haavu[20] or mandalata havu,[15] kolakumandala.[15]

- Tamil – retha aunali, kannadi virian[15] or kannadi viriyan.[21]

- Malayalam – mandali, ruthamandali, manchatti, shanguvarayan, "Rakta Anali"[15]

- Sinhala – thith polonga.[14][15]

- Burmese – mwe lewe.[15]

- Tulu – kandhodi

Geographic range

Found in Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, China (Guangxi, Guangdong), Taiwan and Indonesia (Endeh, Flores, east Java, Komodo, Lomblen Islands). The type locality is listed as "India". More specifically, this would be the Coromandel Coast, by inference of Russell (1796).[1]

Brown (1973) mentions that it can also found in Vietnam, Laos and on the Indonesian island of Sumatra.[17] Ditmars (1937) reportedly received a specimen from Sumatra as well.[14] However, the distribution of this species in the Indonesian archipelago is still being elucidated.[22]

Within its range it can be very common in some areas, but scarce in others.[13] In India, is abundant in Punjab, very common along the West Coast and its hills, in southern India and up to Bengal. It is uncommon to rare in the Ganga valley, northern Bengal and Assam. It is prevalent in Myanmar.[15]

Habitat

It is not restricted to any particular habitat, but does tend to avoid dense forests. The snake is mostly found in open, grassy or bushy areas, but may also be found in second growth forests (scrub jungles), on forested plantations and farmland. They are most common in plains, coastal lowlands and hills of suitable habitat. Generally not found at altitude, but has been reported as far up as 2300–3000 m. Humid environments, such as marshes, swamps and rain forests, are avoided.[2]

This species is often found in highly urbanized areas and settlements in the countryside, the attraction being the rodents commensal with man.[15] As a result, those working outside in these areas are most at risk of being bitten. It should be noted, however, that D. russelii does not associate as closely with human habitation as Naja and Bungarus (cobras and kraits).[2]

Behavior

Terrestrial and active primarily as a nocturnal forager. However, during cool weather it will alter its behavior and become more active during the day.[2]

Adults are reported to be persistently slow and sluggish unless pushed beyond a certain limit, after which they become fierce and aggressive. Juveniles, on the other hand, are generally more active and will bite with minimal provocation.[2]

When threatened they form a series of S-loops, raise the first third of the body and produce a hiss that is supposedly louder than that of any other snake. When striking from this position, they can exert so much force that even a large individual can lift most of its body off the ground in the process.[2] These are difficult snakes to handle: they are strong and agile and react violently to being picked up.[10] The bite may be a snap, or, they may hang on for many seconds.[15]

Although this genus does not have the heat-sensitive pit organs common to the Crotalinae, it is one of a number of viperines that are apparently able to react to thermal cues, further supporting the notion that they too possess a heat-sensitive organ.[23][24] The identity of this sensor is not certain, but the nerve endings in the supranasal sac of these snakes resemble those found in other heat-sensitive organs.[25]

Feeding

It feeds primarily on rodents, especially murid species. However, they will eat just about anything, including rats, mice, shrews, squirrels, land crabs, scorpions and other arthropods. Juveniles are crepuscular, feeding on lizards and foraging actively. As they grow and become adults, they begin to specialize in rodents. Indeed, the presence of rodents is the main reason they are attracted to human habitation.[2]

Juveniles are known to be cannibalistic.[15]

Reproduction

This species is ovoviviparous.[13] Mating generally occurs early in the year, although gravid females may be found at any time. The gestation period is more than six months. Young are produced from May to November, but mostly in June and July. It is a prolific breeder. Litters of 20–40 are common,[2] although there may be fewer offspring and as little as one.[15] The reported maximum is 65 in a single litter. At birth, juveniles are 215–260 mm in length. The minimum length for a gravid female is about 100 cm. It seems that sexual maturity is achieved in 2–3 years. In one case, it took a specimen nearly 4.5 hours to produce 11 young.[2]

Captivity

These snakes do extremely well in captivity, requiring only a water dish and a hide box. Juveniles feed readily on pinky mice, while the adults will take rats, mice and birds.[2] However, many adults do not feed, with one having refused all food for five months.[15] Breeding is not a problem either. On the other hand, they do make quite dangerous captives.[2] When handled, specimens have been known to use their long, curved fangs to bite right through their lower jaw and into the thumb of the person holding them.[10]

Venom

The amount of venom produced by individual specimens is considerable. Reported venom yields for adult specimens range from 130–250 mg to 150–250 mg to 21–268 mg. For 13 juveniles with an average length of 79 cm, the average venom yield was 8–79 mg (mean 45 mg).[2]

The LD50 in mice, which is used as a general indicator of snake venom toxicity, is as follows: 0.08–0.31 μg/g intravenous, 0.40 μg/kg intraperitoneal, 4.75 mg/kg subcutaneous. For most humans a lethal dose is 40–70 mg. In general, the toxicity depends on a combination of five different venom fractions, each of which is less toxic when tested separately. Venom toxicity also varies within populations and over time.[2]

Envenomation symptoms begin with pain at the site of the bite, immediately followed by swelling of the affected extremity. Bleeding is a common symptom, especially from the gums, and sputum may show signs of blood within 20 minutes post-bite. There is a drop in blood pressure and the heart rate falls. Blistering occurs at the site of the bite, developing along the affected limb in severe cases. Necrosis is usually superficial and limited to the muscles near the bite, but may be severe in extreme cases. Vomiting and facial swelling occurs in about one-third of all cases.[2]

Severe pain may last for 2–4 weeks. Locally, it may persist depending on the level of tissue damage. Often, local swelling peaks within 48–72 hours, involving both the affected limb and the trunk. If swelling up to the trunk occurs within 1–2 hours, massive envenomation is likely. Discoloration may occur throughout the swollen area as red blood cells and plasma leak into muscle tissue.[18] Death from septicaemia, respiratory or cardiac failure may occur 1 to 14 days post-bite or even later.[15]

Because this venom is so effective at inducing thrombosis, it has been incorporated into an in vitro diagnostic test for blood clotting that is widely used in hospital laboratories. This test is often referred to as Dilute Russell's viper venom time (dRVVT). The coagulant in the venom directly activates factor X, which turns prothrombin into thrombin in the presence of factor V and phospholipid. The venom is diluted to give a clotting time of 23 to 27 seconds and the phospholipid is reduced to make the test extremely sensitive to phospholipid. The dRVVT test is more sensitive than the aPTT test for the detection of lupus anticoagulant (an autoimmune disorder), because it is not influenced by deficiencies in clotting factors VIII, IX or XI.[26]

In India, the Haffkine Institute prepares a polyvalent antivenin that is used to treat bites from this species.[15]

Subspecies

| Subspecies[1] | Taxon author[1] | Common name | Geographic range[2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. r. russelii | (Shaw, 1797) | Indian Russell's viper[27] | Across the Indian subcontinent through Pakistan and Bangladesh to Sri Lanka. |

| D. r. siamensis | (M.A. Smith, 1917) | Eastern Russell's viper[28] | From Myanmar through Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia and southern China. Also found in Taiwan.[1] |

Taxonomy

Using morphological and mitochondrial DNA data, Thorpe et al. (2007)[29] provided evidence that the eastern subspecies should be considered a separate species, Daboia siamensis

A number of other subspecies may be encountered in literature,[2] including:

- D. r. formosensis, Maki 1931 – found in Taiwan (considered a synonym of D. r. siamensis).

- D. r. limitis, Mertens 1927 – found in Indonesia (considered a synonym of D. r. siamensis).

- D. r. pulchella, Gray 1842 – found in Sri Lanka (considered a synonym of D. r. russelii).

- D. r. nordicus, Deraniyagala 1945 – found in northern India (considered a synonym of D. r. russelii).

The correct spelling of the species, D. russelii has been, and still is, a matter of debate. Shaw & Nodder (1797), in their account of the species Coluber russelii, named it after Dr. Patrick Russell, but apparently misspelled his name, using only one "L" instead of two. Russell (1727–1805) was the author of An Account of Indian Serpents (1796) and A Continuation of an Account of Indian Serpents (1801). McDiarmid et al. (1999) are among those who favor the original misspelled spelling, citing Article 32c (ii) of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Others, such as Zhao and Adler (1993) favor russellii.[1]

In the future, more species may be added to Daboia. Obst (1983) reviewed the genus and suggested that it be extended to include Macrovipera lebetina, Vipera palaestinae and V. xanthina. Groombridge (1980, 1986) united V. palaestinae and Daboia as a clade based on a number of shared apomorphies, including snout shape and head color pattern. Lenk et al. (2001) found support for this idea based on molecular evidence, suggesting that Daboia not only include V. palaestinae, but also M. mauritanica and M. deserti.[2]

Mimicry

Some herpetologists believe that, because D. russelii is so successful as a species and has such a fearful reputation within its natural environment, another snake has even come to mimic its appearance. Superficially, the rough-scaled sand boa, Gongylophis conicus, has a color pattern that often looks a lot like that of D. russelii, even though it is completely harmless.[14][2]

See also

- List of viperine species and subspecies

- Viperinae by common name

- Viperinae by taxonomic synonyms

- Dilute Russell's viper venom time

- Snakebite

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. 1999. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, vol. 1. Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 Mallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G. 2003. True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers. Krieger Publishing Company. 359 pp. ISBN 0-89464-877-2.

- ↑ Daboia russelii at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 2 August 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Russell's or Chain Viper at Wildlife of Pakistan. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Snakes of Thailand at Siam-Info. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Captive Care of the Russell's Viper at VenomousReptiles.org. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Somaweera A. 2007. Checklist of the Snakes of Sri Lanka. Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. PDF at Sri Lanka Reptile. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ "Daboia". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=634422. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- ↑ SurvivalIQ Handbook: Survival Skills - Russell's viper description, habitat and picture - Poisonous snakes and lizards

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Whitaker Z. 1989. Snakeman: The Story of a Naturalist. The India Magazine Books. 184 pp. ASIN B0007BR65Y.

- ↑ Oxford. 1991. The Compact Oxford English Dictionary. Second Edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-861258-3.

- ↑ "Daboia russelii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=634966. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Stidworthy J. 1974. Snakes of the world. Grosset & Dunlap Inc. ISBN 0-448-11856-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Ditmars RL. 1937. Reptiles of the World: The Crocodilians, Lizards, Snakes, Turtles and Tortoises of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. The McMillan Company. 321 pp.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 15.17 15.18 15.19 15.20 15.21 Daniels JC. 2002. Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-566099-4. pp. 252. Pages 148–151.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Brown JH. 1973. Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 U.S. Navy. 1991. Poisonous Snakes of the World. US Govt. New York: Dover Publications Inc. 203 pp. ISBN 0-486-26629-X.

- ↑ Daboia at MSN Encarta. Accessed 26 September 2006. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Murthy, TSN. 1990. Illustrated guide to the snakes of the Western Ghats, India. Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta. 76 pp. ASIN B0006F2P5C.

- ↑ Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society – Checklists of the Snakes of Sri Lanka. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ↑ Belt P, Warrell DA, Malhotra A, Wüster W, Thorpe RS. 1997. Russell's viper in Indonesia: snakebite and systematics. In R.S. Thorpe, W. Wüster & A. Malhotra (Eds.), Venomous Snakes: Ecology, Evolution and Snakebite. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, No. 70:219–234.

- ↑ Krochmal AR, Bakken GS (August 2003). "Thermoregulation is the pits: use of thermal radiation for retreat site selection by rattlesnakes". J. Exp. Biol. 206 (Pt 15): 2539–45. doi:10.1242/jeb.00471. PMID 12819261. http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12819261.

- ↑ Krochmal AR, Bakken GS, LaDuc TJ (2004). "Heat in evolution's kitchen: evolutionary perspectives on the functions and origin of the facial pit of pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae)". J. Exp. Biol. 207 (Pt 24): 4231–8. doi:10.1242/jeb.01278. PMID 15531644. http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15531644.

- ↑ York DS, Silver TM, Smith AA (1998). "Innervation of the supranasal sac of the puff adder" (abstract). Anat. Rec. 251 (2): 221–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199806)251:2<221::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 9624452. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/28319/ABSTRACT?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ↑ Antiphospholipid Syndrome at SpecialtyLaboratories. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ↑ Checklist of Indian Snakes with English Common Names Snakes-Checklist.pdf at University of Texas. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ Daboia russelii siamensis at Munich AntiVenom INdex (MAVIN). Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ↑ Thorpe RS, Pook CE, Malhotra A (2007). "Phylogeography of the Russell's viper (Daboia russelii) complex in relation to variation in the colour pattern and symptoms of envenoming". Herpetological Journal 17: 209–18.

Further reading

- Hawgood BJ (November 1994). "The life and viper of Dr Patrick Russell MD FRS (1727–1805): physician and naturalist". Toxicon 32 (11): 1295–304. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90402-2. PMID 7886689.

- Adler K, Smith HM, Prince SH, David P, Chiszar D (2000). "Russell's Viper: Daboia russelii not Daboia russellii, due to Classical Latin rules". Hamadryad 25 (2): 83–5.

- Breidenbach CH (1990). "Thermal cues influence strikes in pitless vipers". Journal of Herpetology (Society for the Study of Reptiles and Amphibians) 24 (4): 448–50. doi:10.2307/1565074.

- Cox M. 1991. The Snakes of Thailand and Their Husbandry. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida. 526 pp. ISBN 0-89464-437-8.

- Daniels, J.C. Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. (2002). BNHS. Oxford University Press. Mumbai. viii+238pp.

- Dimitrov GD, Kankonkar RC (February 1968). "Fractionation of Vipera russelli venom by gel filtration. I. Venom composition and relative fraction function". Toxicon 5 (3): 213–21. PMID 5640304.

- Dowling HG (1993). "The name of Russel's viper". Amphibia-Reptilia 14: 320. doi:10.1163/156853893X00543.

- Gharpurey K. 1962. Snakes of India and Pakistan. Bombay, India: Popular Prakishan. 79 pp.

- Groombridge B. 1980. A phyletic analysis of viperine snakes. Ph-D thesis. City of London: Polytechnic College. 250 pp.

- Groombridge B. 1986. Phyletic relationships among viperine snakes. In: Proceedings of the third European herpetological meeting; 1985 July 5-11; Charles University, Prague. pp 11–17.

- Jena I, Sarangi A. 1993. Snakes of Medical Importance and Snake-bite Treatment. New Delhi: SB Nangia, Ashish Publishing House. 293 pp.

- Lenk P, Kalyabina S, Wink M, Joger U (April 2001). "Evolutionary relationships among the true vipers (Reptilia: Viperidae) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 19 (1): 94–104. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0912. PMID 11286494. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1055790301909121.

- Mahendra BC. 1984. Handbook of the snakes of India, Ceylon, Burma, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Annals of Zoology. Agra, India, 22.

- Master RWP, Rao SS (July 1961). "Identification of enzymes and toxins in venoms of Indian cobra and Russell's viper after starch gel electrophoresis". J. Biol. Chem. 236: 1986–90. PMID 13767976. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=13767976.

- Minton SA Jr. 1974. Venom Diseases. CC Thomas Publishing, Springfield, Illinois. 386 pp.

- Naulleau G, van den Brule B (1980). "Captive reproduction of Vipera russelli.". Herpetological Review (Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles) 11: 110–2.

- Obst F (1983). "Zur Kenntnis der Schlangengattung Vipera". Zoologische Abhandlungen (Staatliches Museums für Tierkunde in Dresden) 38: 229–35.

- Reid HA. 1968. Symptomatology, pathology, and treatment of land snake bite in India and southeast Asia. In: Bucherl W, Buckley E, Deulofeu V, editors. Venomous Animals and Their Venoms. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press. pp 611–42.

- Shaw G, Nodder FP. 1797. The Naturalist's Miscellany. Volume 8. London: Nodder and Co. 65 pp.

- Shortt (1863). "A short account of the viper Daboia elegans (Vipera Russellii)". Annals and Magazine of Natural History, London 11 (3): 384–5.

- de Silva A (1990). Colour Guide to the Snakes of Sri Lanka. Avon (Eng): R & A Books. ISBN 1-872688-00-4.

- Sitprija V, Benyajati C, Boonpucknavig V (1974). "Further observations of renal insufficiency in snakebite". Nephron 13 (5): 396–403. doi:10.1159/000180416. PMID 4610437.

- Thiagarajan P, Pengo V, Shapiro SS (October 1986). "The use of the dilute Russell viper venom time for the diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants". Blood 68 (4): 869–74. PMID 3092888. http://www.bloodjournal.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=3092888.

- Maung-Maung-Thwin, Maung-Maung-Thwin, Maung-Maung-Thwin, Maung-Maung-Thwin (1988). "Kinetics of envenomation with Russell's viper (Vipera russelli) venom and of antivenom use in mice". Toxicon 26 (4): 373–8. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(88)90005-0. PMID 3406948.

- Mg-Mg-Thwin, Mg-Mg-Thwin, Hla-Pe U (1985). "Relationship of administered dose to blood venom levels in mice following experimental envenomation by Russell's viper (Vipera russelli) venom". Toxicon 23 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(85)90108-4. PMID 3922088.

- Tweedie MWF. 1983. The Snakes of Malaya. Singapore: Singapore National Printers Ltd., 105 pp. ASIN B0007B41IO.

- Vit Z (1977). "The Russell's Viper". Prezgl. Zool. 21: 185–8.

- Wall F (1906). "The breeding of Russell's viper". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 16: 292–312.

- Whitaker R. 1978. Common Indian Snakes. New Delhi (India): MacMillan. 85 pp.

- Wüster W (1992). "Cobras and other herps in south-east Asia". British Herpetological Society Bulletin 39: 19–24.

- Wüster W, Otsuka S, Malhotra A, Thorpe RS (1992). "Population Systematics of Russell's Viper: A Multivariate Study". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 47 (1): 97–113. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1992.tb00658.x.

- Zhao EM, Adler K. 1993. Herpetology of China. Society for the Study of Amphibians & Reptiles. 522 pp. ISBN 0-916984-28-1.

External links

- Daboia russelii at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- DRVVT test information at Lab Tests Online. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Dilute Russell's Viper Venom Time at LabCorp. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Russell's viper at Naturemagics. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Russell's Viper at Michigan Engineering. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Russell's viper at SurvivalIQ. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- When a cobra strikes: Interview with Romulus Whitaker, dated Sunday, June 13, 2004, at The Hindu. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Mark O'Shea in Sri Lanka at Mark O'Shea. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Common Poisonous Snakes in Taiwan at Formosan Fat Tire. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Vipera russelli at Snakes of Sri Lanks. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Video of Daboia russelii at YouTube. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Video of Daboia russelii feeding at YouTube. Accessed 5 September 2007.

- Toxicology